Tax horsepower

The tax horsepower or taxable horsepower was an early system by which taxation rates for automobiles were reckoned in some European countries, such as Britain, Belgium, Germany, France, and Italy; some US states like Illinois charged license plate purchase and renewal fees for passenger automobiles based on taxable horsepower. The tax horsepower rating was computed not from actual engine power but by a simple mathematical formula based on cylinder dimensions. At the beginning of the twentieth century tax power was reasonably close to real power; as the internal combustion engine developed, real power became larger than nominal taxable power by a factor of ten or more.

Contents |

Britain

The so-called RAC horse-power formula was concocted in 1910 by the RAC at the invitation of the British government.[1] The British RAC horsepower rating was calculated from total piston surface area (i.e. "bore" only). To minimise tax ratings British designers developed engines of a given swept volume (capacity) with very long stroke and low piston surface area: British cars and cars in other countries applying the same approach to automobile taxation continued to feature these long thin cylinders in their engine blocks even in the 1950s and 1960s, after auto-taxation had ceased to be based on piston diameters, partly because limited funds meant that investment in new models often involved new bodies while under the hood/bonnet engines lurked from earlier decades with only minor upgrades such as (typically) higher compression ratios as higher octane fuels slowly returned to European service stations.

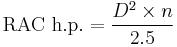

The RAC (British) formula for calculating tax horsepower:

- where

- D is the diameter (or bore) of the cylinder in inches

- n is the number of cylinders [2]

The increasing discrepancy between tax horse-power and actual horsepower, along with some of the other distortive effects on engine design, led to the approach becoming discredited and the British government abandoned it in the 1940s.[1]

Continental Europe

Although tax horsepower was computed on a similar basis in several other European countries during the two or three decades before the Second World War, continental cylinder dimensions were already quoted in millimeters, reflecting the metric measurement system. As a result of roundings when converting the formula between the two measurement systems, a British tax horse-power unit ended up being worth 1.014 continental tax horse-power units.[1]

France

French-made vehicles after the Second World War in particular have had very small engines relative to vehicle size. The very small Citroën 2CV for example has a 425 cc two cylinder engine that weighs only 100 pounds (45 kg), and at the opposite extreme, the high-end Citroën SM has a still modest 2,700 cc six cylinder engine that weighs only 300 pounds (140 kg).

In France, fiscal horsepower survives. However, in 1956 it was redefined: the formula became more complicated but now it took account of cylinder stroke and of cylinder bore, so that there was no longer any fiscal advantage in producing engines with thin cylinders. The dirigiste approach of the French government nevertheless continued to encourage manufacturers to build cars with small engines, and French motorists to buy them. The 1958 French fiscal horsepower formula also took account of engine speed, measured in rpm. The government modified the fiscal horsepower formula again in 1978 and in 1998. Since 1998 the taxable horsepower is calculated from the sum of a CO2 emission figure (over 45), and the maximum power output of the engine in kilowatts (over 40) to the power of 1.6.

Switzerland

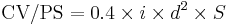

The 26 cantons of Switzerland used (and use) a variety of different taxation methods. Originally, all of Switzerland used the tax horsepower, calculated as follows:

- where

- i is the number of cylinders,

- d is the diameter (or bore) of the cylinder in cm

- S is the piston stroke in cm[3]

The limits between the horsepower denominations were drawn at either 0.49, 0.50, or 0.51 in different cantons. Thus, the eight horsepower category would cover cars of about 7.5 - 8.5 CV. As of 1966, thirteen cantons changed to a taxation system based on displacement (with certain minor differences). In 1973 Berne switched to a taxation system based on vehicle weight, and a few other cantons followed. In 1986 Ticino switched to a system based on a calculation including engine size and weight.[3] Nonetheless, the tax horsepower system remains in effect for seven cantons as of 2007. The plethora of different taxation systems has contributed to there always being an uncommonly wide variety of different cars marketed in Switzerland.

Spain

Fiscal horsepower also lives on in Spain, but is defined simply in terms of overall engine capacity. It therefore encourages small engines, but does not influence the ratio of cylinder bore to stroke. The current Spanish definition does, however, add a factor that varies in order to favour four-stroke engines over two-stroke engines.

Impact on engine design and on auto-industry development

The fiscal benefits of reduced cylinder diameters (bore) in favor of longer cylinders (stroke) may have been a factor in encouraging the proliferation of relatively small six cylinder engined models appearing in Europe in the 1930s, as the market began to open up for faster middle-weight models.[1] The system clearly perpetuated side valve engines in countries where the taxation system encouraged these engine designs, and delayed the adoption of ohv engines because the small cylinder diameter reduced the space available for overhead valves and the lengthy combustion chamber in any case reduced their potential for improving combustion efficiency.

Another effect was to make it very expensive to run cars imported from countries where there was no fiscal incentive to minimise cylinder diameters: this may have limited car imports from the USA to Europe during a period when western governments were employing naked protectionist policies in response to economic depression, and thereby encouraged US auto-makers wishing to exploit the European auto-markets to set up their own dedicated subsidiary plants in the larger European markets.

Taxation can modify incentives and tax horsepower is no exception. Large capacity (displacement) engines are penalized, so engineers working where engine capacity is taxed are encouraged to minimize capacity. This rarely happened in the USA, where license plate fees, even adjusted for horsepower ratings, were comparatively much lower than European car taxes.

Naming and classification of individual car models

The tax horsepower rating was often used as the car model name. For example, the Morris Eight got its name from its horsepower rating of eight; not from the number of cylinders of the engine. British cars of the 1920's and 1930's were frequently named using a combination of tax horsepower and actual horsepower - for example, the Talbot 14-45 had an actual power of 45 hp and a tax horsepower of only 14 hp. The Citroën 2CV (French deux chevaux [fiscaux], two tax horsepowers) was the car that kept such a name for the longest time.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "The Horse-power story". Milestones, the journal of the IAM 23rd year of publication: pages 20–22. Spring 1968.

- ^ Richard Hodgson. "The RAC HP (horsepower) Rating - Was there any technical basis?". wolfhound.org.uk. http://www.designchambers.com/wolfhound/wolfhoundRACHP.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ a b Büschi, Hans-Ulrich, ed (March 5, 1987) (in German/French). Automobil Revue 1987. 82. Berne, Switzerland: Hallwag AG. pp. 96–97. ISBN 3-444-00458-3.

- This entry incorporates information from the equivalent entry in the French Wikipedia at 31 December 2009

- This entry incorporates information from the equivalent entry in the Spanish Wikipedia at 31 December 2009